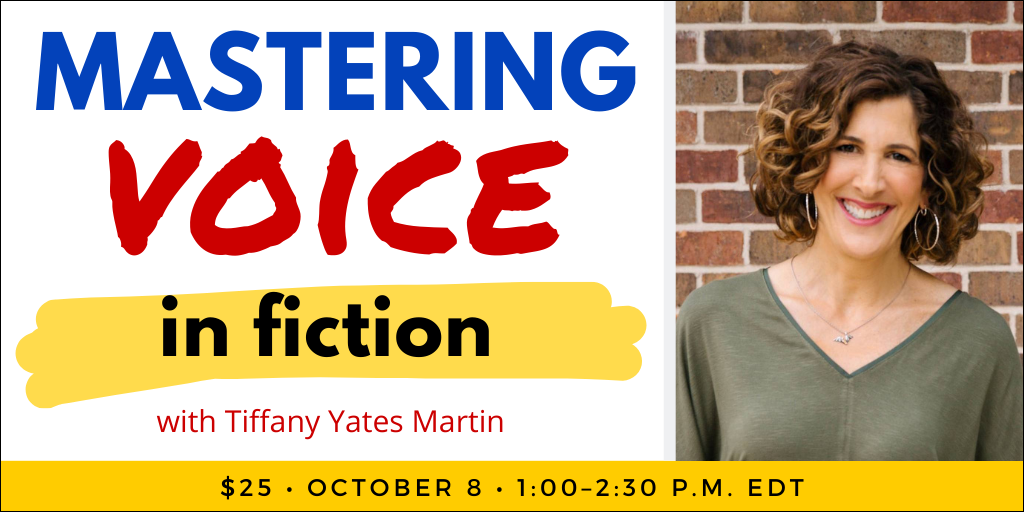

Today’s article is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin Join us on Wednesday, October 8, for the on-line class Mastering Voice in Fiction

One of one of the most constant pieces of guidance writers speak with agents and editors in making their work stand out is that it needs to have voice : solid voice, an one-of-a-kind voice, an engaging voice– or perhaps simply be “voicey.”

Voice is probably among one of the most essential factors in catching the attention of representatives, editors, and readers. As literary representative Amy Collins of Talcott Notch says, “Manuscripts might have crisp, engaging dialogue, glorious descriptive scenes, and a wonderful plot … But none of that issues if the tone of the writing is boring or the voice is not special.”

This is where authors may feel a bit flummoxed. We know voice matters– enormously– in setting our stories apart in a jampacked market. However what the heck is it, and what makes it effective or intriguing or distinctive? And if it’s as well strong or unique, might it not draw attention to itself– like Fergie’s rendition of the National Anthem?

“I understand why writers have problem with it,” Collins admits.

What is voice?

One factor voice is such a tricky concept to grasp is that it’s made use of to refer to three different components of narration: character voice, narrative voice, and writer voice– and they can typically overlap.

Character voice is the means your personalities reveal themselves and their personality. In direct-POV tales (first individual and deep third , where the personality is additionally the narrator, personality and narrator voice are basically the very same.

In indirect POV tales (limited 3rd and omniscient) the narrative voice is distinct from that of the characters and might be neutral and virtually unnoticeable, or unique and even particular. Junot Diaz’s The Brief Remarkable Life of Oscar Wao , for instance, includes a storyteller that is additionally a small personality in the story yet takes an omniscient POV with an one-of-a-kind, solid voice, as does Marcus Zusak’s The Book Thief , told by omniscient, personality-filled Death, additionally a major player in the tale. [Learn more: Choosing Story Perspective: Direct versus Indirect POV]

And overlaying all of that is author voice– probably the most ephemeral and hard-to-define location of voice. Author voice is why, though the characters, setting, style, and approach might be various in each of a writer’s publications, they always have a deeply individual stamp on them of the author’s style– and it’s so commonly why viewers consistently seek out a preferred author’s job.

Author voice has a tendency to be the trickiest, and the one most authors are coming to grips with when they really feel baffled or frustrated by what exactly voice is or means or consists of.

Author voice includes a wide variety of elements: diction and phrase structure, word option and language usage, rhythm and tone, frame of reference and worldview and themes, and a lot more. In short, it’s the author’s individuality and style instilling itself into the job, frequently subtly or without accentuating itself– though not always, as in “metanarrated” tales like William Goldman’s The Princess New bride or Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quijote de la Mancha , where the conceit is that that the writer (or at the very least a fictionalized variation of them) is telling the story straight.

Overwhelmed yet?

Discovering your story’s voice

As you’re tackling your stories, much of their voice will be a creative choice you deliberately make in the kind of the narrative and character voices. What viewpoint do you intend to inform your tale from? What narrative perspective suits your tale and purposes and design? What tone, what strategy, what level of affection are you envisioning?

You might know you want a narrative voice that’s separate from the character voice, for example– the indirect POVs of omniscient or minimal 3rd– to allow you a more comprehensive narrative perspective where to observe and report their actions, thoughts, and the story activity rather than the extra subjective and restricted viewpoint of the personalities themselves.

Or maybe the tale you envision is firmly grown in the direct point of view of one or more of your main characters– they speak with you, you hear their voice currently as the tale plays in your head, and you wish to provide visitors straight access to that experience as they endure the occasions of your story, as if they get on a ride-along.

It’s okay if you aren’t specific initially concerning the most efficient voice for your tale. In composing The Book Burglar , embeded in Nazi Germany during The Second World War, writer Marcus Zusak recognized beforehand what narrative perspective he desired: “Death is ever-present during war, so here was the ideal option to tell Guide Thief ,” he says in an interview in the rear of guide.

However in the beginning, he claims, Fatality was too mean, supercilious and scary, and he didn’t really feel the narrative/character voice was working for the story. He experimented with various other techniques, including altering the POV and narrative perspective, but six months later returned to Death, this time around as a personality existentially wearied of his somber job and “informing this tale to verify to himself that human beings are in fact worth it,” with a looser, also humorous tone.

Shelby Van Pelt came across a key narrative voice in her very first novel as a workout in a writing course to compose from an unusual perspective. When she turned in a quick piece written from the POV of an intelligent, acutely observant, wryly witty octopus, her instructor motivated her to broaden the story, and the outcome– Extremely Intense Creatures — got the focus of agents and authors with Marcellus the octopus’s distinctive opening narrative/character voice, selling for 6 figures in a multi-house auction and ultimately touchdown on the New York Times bestseller listing not as soon as however two times.

Van Pelt has written and spoken of the method Marcellus’s voice revived in her head , forming the narrative, yet her multiple-POV tale likewise features two various other distinct narrative/character voices, each in a different POV, expanding her narrative perspective beyond Marcellus’s aquarium container to allow her more freedom in telling the complete story.

How do you see and hear a specific tale in your head? Where are you “observing” it from? Exactly how do you desire your visitors to experience it? What tone and viewpoint really feels most natural and comfortable to you?

Conversely, what might be an appealing or rewarding narrative voice to attempt to extend you past that convenience area?

Your story as you’re imagining it may recommend the type of solid, particular narrative voice Zusak and Van Pelt chose, or you might want a more objective point of view, like Laurie Frankel’s This Is Exactly how It Constantly Is , a tale informed in an extra neutral omniscient narrative voice that does not draw attention to itself, yet allows viewers accessibility to each personality’s ideas, responses, and feelings and focus on the experiences, independently and collectively, of a family with a transgender kid.

Narrative voice assists establish a tale’s tone, really feel, mood. It guides the reader’s experience of the tale with producing its range and range, how much gain access to the visitor needs to the personality, and what perspective they’re checking out and experiencing it from. It can determine whether your story really feels casual or a lot more formal, intimate or extra removed, unbiased or subjective.

Like so several concerns in craft, there is no “right” answer to which narrative voice is best for a particular tale. It’s simply subjective, based upon lots of personal and stylistic factors. All POVs and viewpoints are possibly valuable (also Death, as Zuzak proved). Present stressful is as preferred as previous, and neither one is much better nor worse, simply different.

The “right” narrative voice is the one that feels right to you for the tale you want to inform, the means you wish to inform it, and the experience you want the reader to have.

Searching for your voice

Yet where does your author voice entered into the mix? If you’ve selected a specific narrative/character voice for your story for the effect it develops on viewers, then isn’t “adding in” your very own personal creative voice a disturbance?

Like the solution to a lot of innovative concerns, it depends.

Zusak talks about reevaluating and brightening his prose “dozens of times” in his writing and alteration process and over lengthy stretches of time, particularly his distinct use of figurative language: “I such as the concept that every page can have a treasure on it,” he states.

Pick up any of his writing and you’ll begin to discover uniformities, even throughout extremely various stories: that use powerful images and metaphorical language, dark motifs and the exploration of large thoughtful concerns with a confident curved, and wit usually laced throughout. He frequently resolves the reader as if bringing us into the characters’ self-confidence, and rotates quick-moving short sentences and paragraphs with longer and extra reflective prose in tales of personalities looking for significance.

Just like most competent writers, Zusak’s authorial voice is unique in all his job, and yet it doesn’t pull focus from or specify the tale itself. It runs below the surface of the story like a bass line: Take it out and you ‘d notice that the story sheds much of its splendor and texture and depth, but while it’s playing you might never also notice it.

Which seems excellent, but just how do you do it?

The tone and style and feeling of our tales, nevertheless deliberately crafted, isn’t something we produce from entire cloth. You’ll never ever discover your own effective authentic voice by copying other individuals or enforcing a crafted voice onto the creating externally; it comes from within. Voice is interfered with and can really feel abnormal when you attempt to “do it.” Intentionally pursuing a voice typically results in sounding like a replica of another person, or rigid and awkward, and even pompous.

Author voice is something you already have, as does every human on earth. The technique is to uncover, establish, and complimentary it on the web page.

See if you can recognize the qualities of your very own writing similarly you would examine other authors’ voice. Do you have persisting motifs in your work? What tone do your stories have a tendency to have– light and funny? deep and lyrical? laid-back and intimate or extra formal? hopeful or negative? or any of a range of infinite opportunities. What kind of language do you have a tendency to utilize: your vocabulary and word choice, the rhythm and size of your sentences, just how you shape the prose with syntax? Are your tales a lot more action-focused or introspective and character-driven?

My stories, as an example (composed under my pen name, Phoebe Fox), have a tendency to check out the topics of household and mercy. They have a tendency to be character-driven, have an obtainable and informal tone, and include humor. In both my fiction and nonfiction writing, I frequently create in intricate sentences with substance conditions and a lot of em dashes and semicolons; I enjoy language and am calculated with word choice, am fairly totally free with imagery and figurative language, and commonly include alliteration along with rhythms of three (as actually this sentence does).

If you can not pinpoint your own authorial voice, ask others to use you their unbiased viewpoint. Ask beta readers, critique partners, or actually any individual willing to review you to identify the tone and feeling of your voice, your style, the character of your writing.

Create a specific passage of another writer’s tale in your very own way– exactly how would certainly you associate that passage? After that write a passage from your very own tales in the design of another writer– a great means to recognize precisely how it’s different from what you normally gravitate to. Try this workout with one more author: Have them write something in what they feel is your voice, while you do the very same for their job– it’s a useful, hands-on means to determine the elements of voice and see what makes each author’s unique.

Your voice may be affected by other musicians’ voices– we’re all formed by our atmosphere, including who and what we like to read. The trick is to let these influences all season and lead to your very own unique mixture, as choreographer Camille A. Brown discusses in her TED Talk Her voice takes motivation and impact from everything from the Jacksons to Broadway musicals to African American social dancing. In choreographing her manufacturing of When on This Island , Brown connected to a specialist in Afro-Haitian dancing, however then used it as a jumping-off point for her very own production. “This has to do with me comprehending the beginnings for myself. So after that I can use my choreographic voice and riff on that,” she states. “And after that when it appears, it’s something that is Camille and not someone else’s.”

Each of us includes wide varieties, and you can use various elements of your writer voice from tale to tale, equally as we access various aspects of our character in numerous social teams. And your author voice may evolve as you grow your understanding of craft and as you grow as a person.

Final ideas

As Amy Collins states, “Authors require to identify and lean right into their voice so that their scenes and phases are not neutral and off-white. The authors might have one-of-a-kind backstory or spins, however if the voice is null or boring, after that I am out.”

Voice takes nerve and self-confidence and technique. Depend on that you suffice– your authentic self. It may not be Hemingway or King or Saunders or whoever you admire, however we currently have that. What the globe does not have is you and your unique, particular, special voice.

Keep in mind from Jane: If you appreciated this blog post, be sure to join us on Wednesday, October 8, for the on-line course Mastering Voice in Fiction

Tiffany Yates Martin has actually invested her whole profession as an editor in the posting sector, working with major publishers and New York Times , Washington Article , Wall Surface Road Journal , and United States Today bestselling and prize-winning authors in addition to indie and newer writers. She is the founder of FoxPrint Editorial (called among Writer’s Digest’s Ideal Websites for Writers) and author of Intuitive Editing: An Imaginative and Practical Guide to Modifying Your Creating and her most recent, The Instinctive Author: Exactly How to Grow & & Sustain a Better Composing Job She is a regular contributor to writers’ electrical outlets like Author’s Digest, Jane Friedman, and Writer Unboxed, and a constant speaker and keynote audio speaker for authors’ companies around the country. Under her pen name, Phoebe Fox, she is the writer of 6 books.