Photograph by Grace Byron.

July 6, 2024

My obsession with horseshoe crabs started small. D. and I went to the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge on a bird walk. The two women next to us turned out to work at an independent competitor to the massive plushie company Squishmallow, and I listened to them talk about the qualities of superior felt as D. watched an egret scarf down an eel across the marsh. Both of us grew up in the Midwest, but it’s D. who loves birding and camping. I enjoy nature as much as the next woman, but I love the feeling of returning to a solid bed surrounded by four sturdy walls. It wasn’t until we walked back to the nature center, stocked with stuffed animals both real and fake, that I came alive. Eagles, hummingbirds, owls, and mice, all lined up in glass cages and offered as stuffies, intended for kids below the age of ten. I idly wound up a small, plastic horseshoe crab and watched it race along the linoleum. Then we turned the corner into a boardroom and discovered a small exhibit on the crabs, a series of nightscape photographs depicting hordes of the ancient critters scampering under streetlights on the beach. The four-hundred-million-year-old hard-shell survivors mating, spawning, and molting on the beach at night under the streetlights, unbothered by the dawn of new technology.

The strange, spiderlike crabs looked uncanny, with shells like the backs of stingrays. Their barnacles and the years of life they’d spent living underwater, chowing down on tiny fish and algae, lent them a gray-green hue. Like Paleozoic monsters, alien crustaceans knocked out of time and space. They inspired the same fear and delight that walking in the woods once did when I was a child: the fear and delight of discovery.

Most people come to horseshoe crabs through their interest in birds, not the other way around. The crabs’ tiny blue eggs are key to the migration patterns of birds like red knots who feast on the translucent orbs. But because the crabs are harvested for medical research, red knots are quickly becoming an endangered species, with their numbers dwindling by over ninety percent in the past forty years.

Unlike humans, horseshoe crabs have a natural ability to fight pathogens due to the special clotting ability of their blood. Ever since biomedical companies discovered this trait, they’ve bled the horseshoe crabs en masse in order to further their research. Many vaccine breakthroughs have occurred due to the help of these oceanic close cousins of arachnids.

New York does not allow the harvesting of horseshoe crabs for research, but nearby states, like Maine, do. While around ten to thirty percent of those in custody eventually die, bleeding isn’t usually what kills them; it is the wear and tear of captivity. Those let back into the ocean are often lethargic and more susceptible to disease. All of this, even though there are now synthetic options that replicate the endotoxic qualities of horseshoe crab blood. It sounds like the premise of a cheesy horror movie: an innocent alien species harbors the cure to a deadly disease set to wipe out a more aggressive species. In essence, it’s extraction.

During horseshoe crab season, between May and June, there are a few small festivals held in their honor. It’s easy to anthropomorphize them. Even more so after I see the little stuffed animals in their likeness. I want to take one home. I want to hold one, to cradle something from the deep.

May 18, 2025

I dragged D. and a few of my friends out to Broad Channel Park. We walked past a few laminated signs detailing horseshoe crab life cycles, food webs, and calls for more protective legislation before stumbling on a series of tables manned by rangers and wildlife specialists. A poster decorated brightly with clip art welcomed us to the Annual Horseshoe Crab Festival. Information surrounded us: hastily written handouts, screeching chatter, petitions.

One woman in sunglasses with a tiny slate-gray horseshoe crab plushie taught us how to handle the creatures.

“When you get down to the beach, you’ll see them. You want to grab them by the shell on both sides. Never by the tail—that’s how they sense things and flip themselves over. Never by the hinge, ’cause when they close, that can hurt.”

She motioned to a lanky, twenty-something guy a table down.

“You can do it with a ranger over at that station if you want to try it out first.”

We walked over to the murky tank and peered inside at the living horseshoe crab. The bored worker just said, “When you get down there, you can handle them.” Perhaps he was tired from the stream of children. He figured we were adults; we could handle it without a test drive.

The thing they don’t tell you—or only refer to obliquely, maybe due to the throngs of children in attendance—is that the hordes descend during high tide and full moons because the crabs are mating. The “season” is a euphemism for their fertility ritual.

Dozens of well-meaning families and amateur naturalists crowded the small patch of sand. Some scanned the horizon for birds, desperate for a new sighting to mark on their Merlin app. When we got to the edge of the pebbly water, we could make out dozens of stone-colored crabs attached to one another head-to-butt, like half-moons washed up on the shore. They were mating in a frenzy, even if it looked more like a huddle.

I waded into the water to get a better look at the crabs. Up close, they’re a bit like mechanized stingrays, with legs lurking underneath. A horseshoe crab’s underbelly looks like a giant bug, as spiderlike as their arachnid classification would suggest. They use their legs to swim and scuttle around on the sand, leaving strange marks in their wake.

As I watched the crabs mate, they looked almost entirely immobile, shifting only with the current. The males were smaller than the females, and sometimes multiple males attached themselves to a single female. (“That’s their sex, not their gender. We don’t know their gender,” one ranger joked. I looked away, naturalist humor notwithstanding.) Under the clear sky, my friends and I chased the crabs around, each wondering who would dare to pick one up first. It was me. The crab I picked up seemed worse for the wear. Its little legs were still as I lifted it out of the water, and a large portion of its shell was missing. I shivered, trying not to think about the fact that I may have just picked up a carcass. I gently set him back in the sand.

Before we left we waded out onto the concrete beneath the highway so that D. and Ashe could try to spot the elusive red knots.

“Is that one?” I asked, pointing to a few bare trees in the distance, right above a group of fishermen drinking Corona.

“Maybe,” D. said. “Maybe.”

I had done what I needed to do: I had held a horseshoe crab. Afterward, we drove to Roll-n-Roaster, a diner in Sheepshead Bay, and drank black-and-white shakes with roast beef sandwiches. A triumph.

Photograph by Grace Byron.

June 9, 2025

On a gray, drizzling evening in early summer, we made our way over highway bridges and past the fading neon signs in Canarsie.

“We’re going horseshoe crabbing,” I said.

“But we’re not”—Agnes looked around—“crabbing, are we?”

“No,” I said. “I guess not.”

There is not a great verb to describe what we were doing on the overcast beach just as high tide began to lap against the shore. Monitoring? Helping? Observing?

I had decided to try and volunteer—or at least tag along—during a horseshoe monitoring session with the NYC Bird Alliance. The goal was to count, tag, and check on the population during high tide. This time we’re at Plumb Beach, and it’s Ashe and Agnes, who both have cars, accompanying me.

There are, of course, important reasons to monitor horseshoe crabs. They are protected from being harvested for medical purposes in New York, but many other states have refused to enact the same policies; some people even make use of them twice, once for medical research and once for bait.

I settled on “volunteering,” and we marched past the porta-potty and over the sand, toward a dozen or so volunteers congregating around a short, clear-voiced woman in tiny glasses and a bright red coat, with wisps of silver hair tied back behind her head. The more data the group logged, she explained, the more accurate their reporting on horseshoe crab population trends would be. All of this is important for grant writing; the nonprofit world thrives on numbers. (Of course, the mood around funding for scientific research was sour; jokes were made by the amateur naturalists about the current administration’s anti-vaccination policies.)

Ann Seligman often works with the NYC Bird Alliance. (Her email sign-off is simply “Horseshoe Crab Aficionado.”) My friends and I were late to the party that night, and she pointed this out. “I’m about halfway through my spiel,” she told us. She was exactly how I imagined a wildlife teacher at the University of Vermont would be. Apparently, her neighbors have complained about the fishy smell of her car in their shared garage. She showed off a small souvenir her husband gifted her: a special kind of knife that helps untangle fishing wire.

Agnes and Ashe waited behind, picking up trash as Ann gave us the outline of our night. She kept checking her watch, waiting for the precise moment of high tide: 7:29 P.M. Using two white pipes connected into a square, we prepared to survey the number of horseshoe crabs present that night at random. The pace at which we had to stop and check for critters was a bizarre math problem that I couldn’t quite follow. Meanwhile, two volunteers carried clipboards to note the number of horseshoe crabs in the sample field. I looked around. So far there weren’t so many. As requested, we looked around and grabbed the numbers of those already tagged.

“Alright, we still have a few minutes,” Ann called out. “But get ready.”

Ashe and Agnes were nowhere to be found, off looking at birds with sketchbooks in hand.

Meanwhile, Ann told everyone a story about a man who stuffed a turtle in his pants at JFK, hoping, apparently, to smuggle the beast onto a plane. “The crazy thing was that it was the most common species,” she paused, as if waiting for us to jump in. “A red slider!”

Then we were off.

Magically, the crabs started washing ashore almost exactly at high tide. Just a few at first, around 7:34 P.M., several singles and one or two mating pairs. We watched one couple, walking on the beach, try to pick one up by its tail. A volunteer ran over and stopped them. Ann shook her head.

The volunteers who were selected to put down the white square and take notes were way ahead of us. Their step count determined how far they were supposed to tread between samples.

Our objective was simple: to watch. We were allowed to turn over capsized crabs, stuck by the tide, and we could take pictures of tagged crabs, but there were almost too many people here for the work we had to do. It seemed more people wanted to commune with nature than were entirely necessary. Nonetheless, we walked dutifully over the jetties and dunes, logs and rocks, plants and shells.

“The crabs we tag are often found in Long Island,” Ann said, “like city kids going to the ’burbs.”

Soon we saw dozens, and then dozens more. During the whole walk we must have seen hundreds. They came ashore in every mating variation possible. Threesomes, foursomes, sixsomes. Orgies of spidery crabs crawled and attached. We saw dead crabs too, sometimes just empty shells or amber-y molts, washed ashore motionless like sacrifices to the gods.

The surf bubbled up around the flotsam and jetsam, stranding little barnacled crustaceans at our feet. Foolishly I had worn hiking boots instead of the sandals I had originally decided upon. We carried on, smiling, our legs wet, stepping over the female crabs digging deep in the sand while males approached them from behind.

Ann picked up a crab and showed us its legs up close. Some of their limbs weren’t for mobility; they worked like claws to bring food close to their mouths, located in the center of their bodies. Agnes dropped a sea snail into the beast’s mouth, and we watched the crab devour it in seconds.

We came across the bloated corpse of a raccoon floating back and forth, caught on a capsized log. It was beautiful, in death, the mirage of its white-and-gray fur, the slight remnants of its bandit mask.

There was plenty of death, in all its majesty: a dead rat with giant teeth that looked like it had been struck by lightning. A man-of-war gently spreading its translucent tentacles near the shore. Of course, there were also many live crabs. Their shells littered the beach. I almost asked if we were allowed to take them with us, but I thought better of it. Another time.

A few crabs needed to be flipped, and some we just watched crawl along the sand, making indents on either side where their shells hit the ground. When orgies formed, they looked like crop circles, as alien as nature can appear to the human eye.

When the indigo night fell and we scared away the oystercatchers, Ann told us we were going to tag some crabs.

“Go pick some up! Females if you can.”

She was heavy. I picked her up and ran back toward the group, setting her down with a clunk so we could measure her shell. I couldn’t bring myself to use the drill, but Agnes had no such fear. She got to work, setting the tag in the little hole and returning the crab to the water.

“Does it hurt?” someone asked Ann.

“I don’t think so. One time we set a crab down, and he immediately went back to mate.”

We aligned the crabs one by one along a ruler before tagging them, measuring the length of their murky, gray shells. The drill crushed through the exoskeleton with ease. It doesn’t take much. Ann assured everyone the crabs were fine, even as a few of us flinched in horror. The tag didn’t need to be wrapped around or tied on; it fit exactly in the hole. They looked so fragile trying to scurry away from us. So cute.

In a Bookforum review of Sianne Ngai’s Our Aesthetic Categories, Adam Jasper writes, “Cute is the kind of porn you can enthusiastically consume in public.” Enjoying nature can easily turn into consumption. We walk through the woods looking at birds in order to catch them all, like these animals are Pokémon. Collecting pictures and rummaging for mementos. This is different from witnessing, the act of taking things in without judgement. I cannot say I am overly familiar with the latter mode. Still, our expedition on the cloudy beach felt alien enough to me that, despite taking copious pictures, I couldn’t consume the experience. I had to live it.

After we tagged fifteen crabs, it was time to head back.

“I feel bad that I didn’t get to talk to you,” Ann said, pulling me aside before returning to her work.

“It’s fine,” I said. “I got to see it all happen.”

She was trying to help a horseshoe crab tangled up in fishing line. Time for first aid.

We returned to Roll-n-Roaster to order sandwiches, chicken tenders, fries, and a black-and-white shake. Halfway through our meal, D. messaged me to say they had locked themself out in the rain while doing laundry. So we hit the road again, back to the other side of Brooklyn, where only raccoons rummage around after midnight.

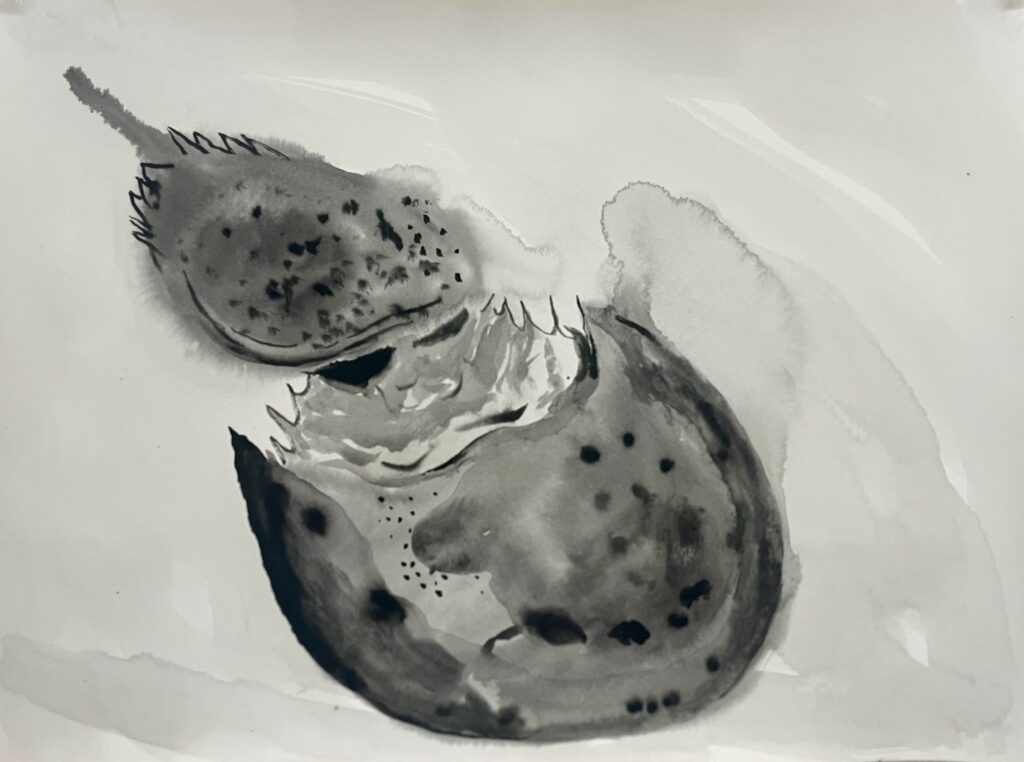

Drawing by Agnes Walden.

Grace Byron’s writing has appeared in The New Yorker, New York Magazine, Bookforum, The New Republic, and elsewhere. Her debut novel, Herculine, is forthcoming from Simon & Schuster in October.